Acute Scrotum

See AUA Medical Student Curriculum: Acute Scrotum

Definition

- Acute scrotum refers any new onset of the following (or combination) of symptoms (3):

- Pain

- Swelling

- Tenderness of intrascrotal contents

Differential diagnosis

- Differential diagnoses include (14):[1]

- Testicular appendage torsion

- Acute epididymitis/epididymo-orchitis

- Spermatic cord torsion

- Strangulated/incarcerated inguinal hernia

- Scrotal cellulitis

- Fournier gangrene

- Idiopathic scrotal edema

- Intratesticular hematoma

- Testicular rupture

- Scrotal or testicular abscess

- Varicocele

- Testicular infarction

- Testicular neoplasm

- Henoch-Schonlein purpura

- Torsion of the appendix testis is the most common diagnosis followed by spermatic cord torsion, epididymitis

- Although all of these diseases can occur at any time during childhood,

- Torsion of the appendix testis is typically most common after infancy and before puberty

- Epididymitis and spermatic cord torsion are most common in the perinatal and pubertal periods

- Torsion of an appendage and epididymitis are managed conservatively with limited consequence

- Prompt surgical exploration for spermatic cord torsion is imperative because the gonad is at considerable risk of ischemic damage or loss

- Although all of these diseases can occur at any time during childhood,

Spermatic Cord Torsion

Acute Intravaginal Spermatic Cord Torsion

Epidemiology

- May occur at any age

- Vast majority of cases occur after age 10 years with a peak at age 12-16 years

- Left-sided predominance

Risk Factors (3)

- “Bell-clapper deformity” wherein the tunica vaginalis abnormally fixes proximally on the cord, resulting in excess mobility of the testis

- Familial predisposition

- Cryptorchid testes

Diagnosis and Evaluation

History and Physical Exam

- History

- The inciting event for torsion is unknown

- History of prior episodes may be elicited

- Nausea/vomiting occurs in 10-60% of boys

- Dysuria and fever are uncommon

- Physical exam

- Most common physical findings (4):

- Generalized testicular tenderness

- Abnormal (horizontal) orientation of the testis

- High-riding testis from a foreshortened cord

- Absent cremasteric/genitofemoral reflex

- Elicited by scratching the inner thigh with resultant testis elevation

- Normally present age >2 years

- Some studies report reduced or absent reflex in all cases of testicular torsion, but intact in up to 10% of proven cases of torsion in other series

- Scrotal edema and erythema may be present, depending on the duration or degree of torsion.

- Most common physical findings (4):

Labs

- Urinalysis +/- culture

- Rule out infectious cause of acute scrotum

- CBC

- Rule out infectious cause of acute scrotum

Imaging

- Before the advent of reliable and rapid scrotal imaging, immediate scrotal exploration was routine

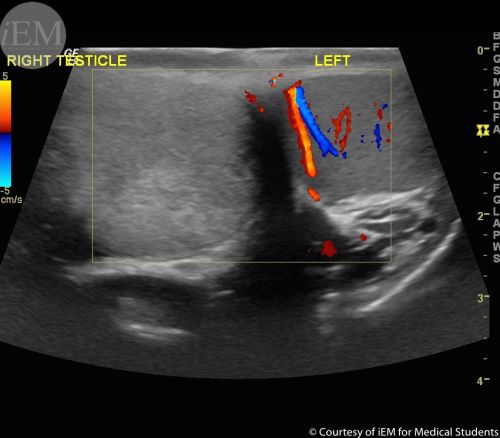

- Doppler Ultrasound

- Findings consistent with testicular torsion (2):

- Reduced or absent Doppler color or waveforms

- Parenchymal heterogeneity compared with the contralateral testis

- Findings consistent with testicular torsion (2):

Management

- Surgical emergency

- Risk of orchiectomy based on onset of pain

- 0-6 hours: 5%

- 7-12 hours: 20%

- 13-18 hours: 40%

- 19-24 hours: 60%

- 24-48 hours: 80%

- >48 hours: 90%

- Irreversible ischemic injury to the testicular parenchyma may begin as soon as 4 hours after occlusion of the cord.

Option

- Orchiopexy

- Manual detorsion can be attempted. However, manual detorsion may not totally correct the rotation that has occurred and prompt exploration is still indicated

Orchiopexy

- Technique

- Equipment

- Sutures

- 3-0 Vicryl x 4

- 4-0 PDS x 6

- 4-0 chromic x 1

- If orchiectomy, 2-0 silk ties to ligate vas deferens and vessels

- Sutures

- Antibiotics

- Cefazolin

- Position: supine

- Incision: midline raphe, length of largest testicle that needs to be delivered

- Surgical plan[2]

- Outline an incision in the midline raphe. Incision should be large enough to deliver twisted testicle.

- Dissect towards twisted testicle. Use scalpel to make skin incision. Continue to divide layers of scrotum towards testicle.

- Deliver twisted testicle. Open the tunica vaginalis and deliver the testicle

- Untwist the testicle. Ensure proper orientation with lateral sulcus being lateral. Feel spermatic cord to ensure no more twists

- Median degree of rotation was 540° in orchiectomy testes and 360° when the testis was salvaged

- Attempt salvage of twisted testicle. Wrap twisted testicle in warm saline

- Deliver contralateral testicle. Repeat steps 2-3 on contralateral (healthy) testicle. Bring contralateral healthy testicle to midline incision.

- Orchiopexy to reduce the risk of metachronous torsion.

- Trim excess tunica vaginalis. Obtain hemostasis along the edge with careful fulguration.

- Reapproximate tunica vaginalis. Evert tunica vaginalis and reapproximate edges behind testicle, in Jaboulay fashion, with running 3-0 Vicryl

- Place three 4-0 PDS interrupted sutures through the everted tunica. Then place these sutures into the dartos of the posterior scrotal wall. Replace the testicle into the hemiscrotum and tie sutures.

- Note that this method does not penetrate the blood-testis barrier with the suture needle and may reduce the risk of forming anti-sperm antibodies[3]

- Evaluate twisted testicle for salvageability. If not salvageable, divide vas and vessels separately with 2-0 silk ties. If salvageable, perform orchiopexy similar to above. In cases of orchiectomy, prosthesis placement is usually offered after complete healing or later in puberty

- Reapproximate dartos. Use 3-0 Vicryl to reapproximate dartos.

- Reapproximate skin. Use 4-0 chromic suture with horizonal mattress to reapproximate skin

- Inject local anesthetic. Local anesthetic solutions containing epinephrine should never be used to anesthetize the penis, scrotum, or spermatic cord.[4]

- Apply dressing

- Equipment

- Post-operative follow-up

- Limit contact sports for 2 weeks or until pain free

- Perform wound check in 3-4 weeks

- Advise of risk to solitary testicle, consider

- Cup protector in high-risk activities (catcher in baseball team)

- Sperm banking in case other testicle is affected

Prognosis

- Subtle abnormalities of semen quality are common

- Semen density is often within the normal range

- Global testicular dysfunction may exist after torsion

- May be due to ischemia-reperfusion injury after release of testicular torsion

- Hypothesis of an autoimmune phenomenon has been dispelled

- Serum FSH, LH, and testosterone were within the reference range.

- May be due to ischemia-reperfusion injury after release of testicular torsion

Intermittent Intravaginal Spermatic Cord Torsion

Diagnosis and Evaluation

- Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion unless the testis is noted to untwist

- Physical exam

- Scrotal swelling or nausea and/or vomiting may or may not be present

- A normal vertical testicular orientation is most common

- Whirlpool sign or an abnormal boggy cord and pseudomass formation below the twisted spermatic cord may also signify intermittent torsion

Management

- Once the condition is confirmed or highly suspected, elective bilateral orchidopexy is indicated to avert torsion and possible organ loss.

- Patients and parents should know that absolute confirmation of the diagnosis may not be possible and that symptoms may persist postoperatively.

Extravaginal Spermatic Cord Torsion (Perinatal Testicular Torsion)

- Perinatal spermatic cord torsion is a term applied to infants regardless of whether the event occurred prenatally (hours, days, weeks, months), during delivery, or postpartum.

- Torsion of the entire cord occurs before fixation of the tunica vaginalis and dartos within the scrotum (extravaginal).

- Most commonly occurs well before delivery, yielding a “vanishing” testis or a hemosiderin-containing nubbin in the scrotum or less commonly in the inguinal canal.

- The testis that sustains loss of blood supply close to delivery is a hard, painless testis fixed to the overlying erythematous or dark scrotal skin with or without edema

- [Urgent exploration is not needed.] However, if torsion is suspected after a normal postnatal scrotal examination, then prompt exploration should be performed as for intravaginal torsion. If torsion is confirmed, contralateral scrotal exploration with testicular fixation should be performed.

Torsion of the Appendix Testis and Epididymis

- Appendix testis

- From the müllerian duct

- Present in 76-83% of testes

- Appendix epididymis

- From the wolffian duct

- Present in 22-28% of testes

- The peak age at occurrence is 7 to 12 years

- Diagnosis and Evaluation

- History and Physical Exam

- Physical Exam

- A “blue dot sign”, a discoloration at the upper pole of the testis representing the ischemic appendage, may be seen through stretched scrotal skin

- Physical Exam

- Imaging

- US

- The normal appendix testis contains no internal blood flow, whereas the twisted appendage may appear as an ovoid hyperechoic, hypoechoic, or heterogeneous nodule without blood flow

- CDUS rarely demonstrates an abnormal appendage but commonly shows hyperperfusion of the epididymis.

- US

- History and Physical Exam

- Management

- Torsion of an appendage is a self-limited process; surgery is rarely indicated

Epididymitis

- Symptoms have a more insidious onset than torsion of the cord or an appendage but may be present rapidly

- The cremasteric reflex should be intact

- The majority of infants with epididymitis have sterile urine and apparently radiographically normal urinary tracts.

- The management goal is to relieve inflammation and any associated infection

- In a prepubertal child with a positive urine culture, renal US and VCUG are indicated (different than elsewhere that only describe a renal US for child with first UTI)

References

- Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA (eds): CAMPBELL-WALSH UROLOGY, ed 11. Philadelphia, Elsevier, 2015, chap 21

- Velasquez, James, Michael P. Boniface, and Michael Mohseni. "Acute scrotum pain." (2017).